I’ve been try ing to remember when I first read The Lord of the Rings and it must’ve been when I was ten or so, meaning in 1976 or early 1977. I say this because my dad bought me The Silmarillion for Christmas and it was published in September 1977. That means I read The Hobbit when I was nine or so. Coming up on 59 next year, it means I’ve been reading Prof. Tolkien’s work for nearly fifty years.

ing to remember when I first read The Lord of the Rings and it must’ve been when I was ten or so, meaning in 1976 or early 1977. I say this because my dad bought me The Silmarillion for Christmas and it was published in September 1977. That means I read The Hobbit when I was nine or so. Coming up on 59 next year, it means I’ve been reading Prof. Tolkien’s work for nearly fifty years.

I assume I came across The Hobbit on my dad’s shelf next to his living room chair. It’s where he kept the various books he was reading at any given time. His habit was to stay downstairs till midnight or one, reading and listening to WQXR, the New York Times’ old classical station. I’d definitely read it before November 1977 when the Rankin & Bass The Hobbit premiered. As a side note, my dad tried to get our first color TV before it aired, but he wasn’t able to.

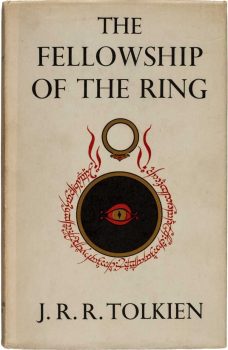

I didn’t read LotR right away, but when I did, I found myself in competition with my dad to finish them. With only the single set of books in the house, we read them in tandem. I remember rushing home from church to see if I could grab The Fellowship of the Ring before my dad had finished reading The New York Times that morning. Even though some days I got the book before him, he read faster and more often and finished several days before me. Hey, I was only ten.

I grew up on fairy tales of all sorts, but particularly the unexpurgated Brothers Grimm stories. Lots of death, murder, cannibalism, witches, and demons were my standard fare. The editions we had were profusely and grotesquely illustrated. Those sorts of stories plus books like the D’aulaires Book of Norse Myths, meant by the time I read The Hobbit, I was ready and well-primed for it.

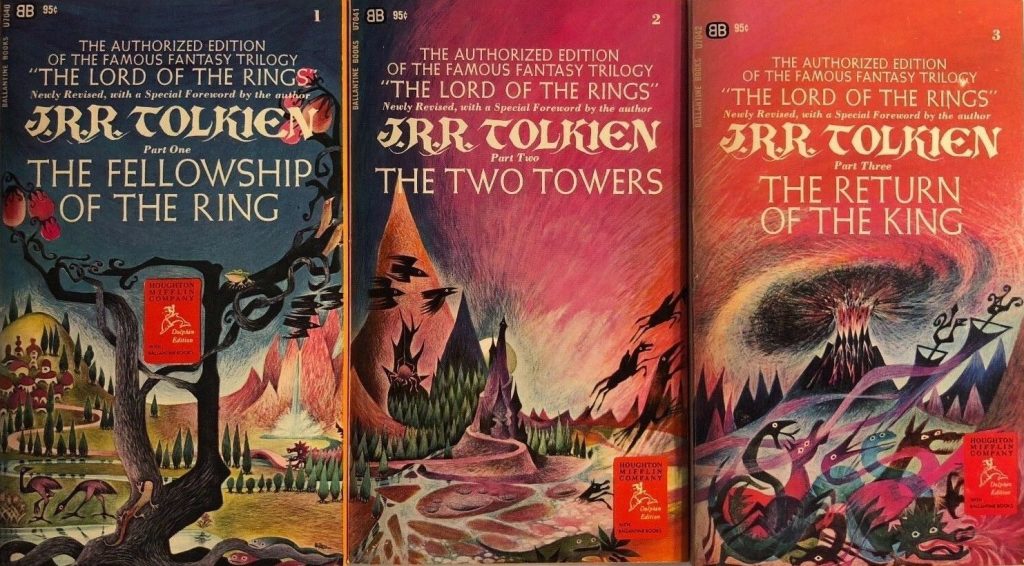

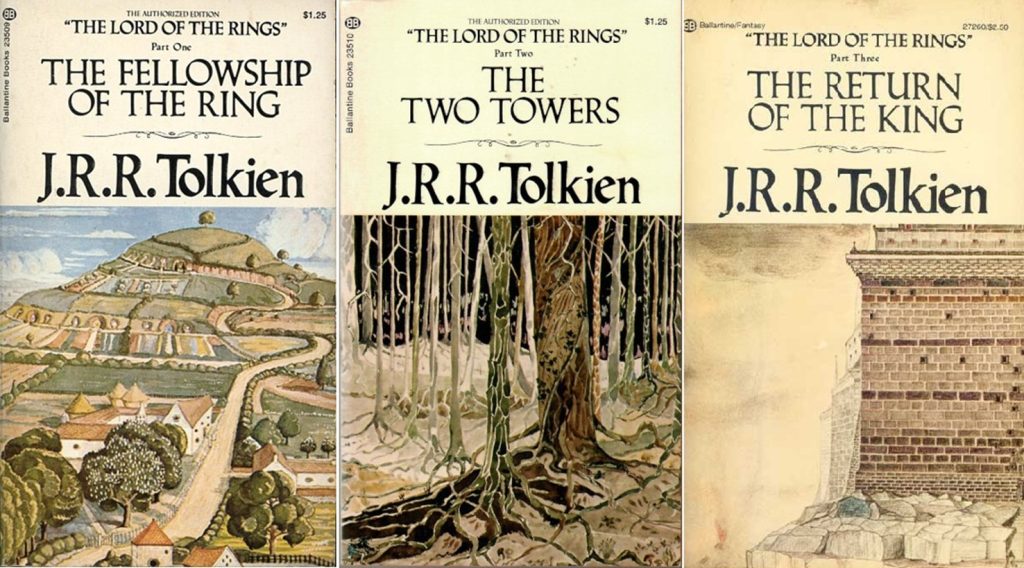

It remains a great read, and easily one of the most memorable fantasy stories I read early on. In Bilbo Baggins, Tolkien created the perfect stand-in for young readers. A bit naive, a bit scared of the dark, and, still, ready and waiting for adventure. Everything past the Shire’s boundaries was as new and enthralling for me as it was for him. The book is so vivid and so impressed on my mind from my very first read, if not word-for-word, I think I could do a pretty good job retelling the story from the very beginning. Fairy tales, I knew, were old stories, told and told again over the centuries. The Hobbit, even if it drew on that folklore tradition, was an original story and it whetted my appetite for more. It’s a straight line from that book to all my other fantasy reading over the following half-century. Before it pointed me to Moorcock, Wagner, and Howard, though, it pointed me to The Lord of the Rings. And in my case, that meant the editions with Barbara Remington’s phantasmagorical cover illustrations.

I spent some time puzzling over them trying to connect them to Tolkien’s prose. Sure, that’s Hobbiton to the left, Shelob’s lair and the Nazgul in the center, and Mount Doom and a battle on the right. They’re so stylized, though, that I wasn’t quite sure what to make of them. I mean, are those cassowaries on the cover of Fellowship? What’s that running through the woods? What is going on?

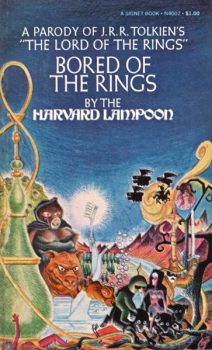

They, more than any of the covers since, are The Lord of the Rings covers for me, though. Those with Tolkien’s own paintings are fine, but the others are all too precise or realistic. Remington’s preserve the strangeness that the stories held me for me the first time I read them. My visions of Moria, Orthanc, and Minas Tirith were unburdened by decades of storytelling set in mock-medieval European settings. They rose off the page like the alien creations they were. The Hobbit and LotR were the first actual fantasy books I read. Fairy tales are set in fairy tale land, hazy and indistinct in their settings. Tolkien’s stories were the first I can recall that were set in lavishly described realistic landscapes with protagonists with some sort of characterization that went beyond stalwart prince or cunning soldier and mixed it with barrow wights, sword-wielding demons, and oathbreaking ghosts. That they’re also the basis for the original cover of the parodic Bored of the Rings only reinforces my love for them.

Tolkien and his books were just becoming commercialized when I first read them. The Brothers Hildebrandt produced several extremely well-selling calendars. Everyone and his brother wrote encyclopedias of Middle-earth or books explaining just what Tolkien meant. The extreme end of this trend was, I’d argue, the careful creation of The Sword of Shannara (read my review here), followed by stacks of books wherein doughty commoners trudged into some dark lord’s land accompanied by a small band comprised of elves, dwarves, and men.

Everyone I was friends with, by which I really mean everyone, read, or at least tried, to read Tolkien. We were all proto-fantasy nerds and it was great. The books were everywhere and I loved it. It felt like I was part of some special order that was privy to something extraordinary. Looking back, I think that was true.

When I told the luminous Mrs. V. how old I was when I read LotR, she asked me if I understood it. Without hesitation, I said yes. I did understand it, but mostly on a basic level, as an exciting tale of adventure filled with magic and monsters. What I missed at ten, came with later readings; an overwhelming sense of a fading world which darkness threatens to overwhelm and endlessly eroding the strength of those arrayed against it.

All the ruins and tombs that littered the land around the Shire are the broken remains of realms lost to the darkness. Vast swaths of Middle-earth are devoid of civilization and population having been devastated in past wars, barbarian invasions, and by plague. Some of the greatest powers that have stood against Sauron for thousands of years have decayed in the case of Gondor or succumbed to his temptations as has Saruman.

Reading The Silmarillion the first time around was mind-boggling. It was not the book I was expecting at all. It was a collection more like the collections of Norse and Greek myths I read than Tolkien’s previous novels. I wanted more LotR and instead, I got the Old Testament of the Elves. Notwithstanding, I got my first sense that Middle-earth was a broken world — quite literally in The Silmarillion. It was a place where evil constantly lurked and sometimes even marched out of its strongholds and crushed everything. It was a place where pride and arrogance constantly led to downfall and self-destruction. I got my first hint of what I had missed that first time around in LotR.

Tolkien described the book as “fundamentally religious and Catholic.” With further readings, while I might not have gotten that explicitly, I did see the moments of grace and Christ-like sacrifice that were essential elements of The Lord of the Rings. That they were manifested in a fallen world made them only more powerful. It became clearer with each reading that LotR was more than an epic adventure story. I’ll explore these in future articles about the individual volumes over the next few months. You see, I’m in the midst of another read of LotR, inspired by a rewatch of Peter Jackson’s movies.

I put Jackson’s Fellowship of the Ring on a few weeks ago for background noise and was immediately reminded of how much I’ve come to dislike it and its sequels. Again, I’ll go into more detail in later pieces, but suffice it to say, my distaste was enough to inspire me to pull out the real thing, open the cover and read those first lines:

When Mr. Bilbo Baggins of Bag End announced that he would shortly be celebrating his eleventy-first birthday with a party of special magnificence, there was much talk and excitement in Hobbiton.

In future installments I’ll write about the individual books of The Lord of the Rings; The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King (if you’re very good, I’ll write about Bored of the Rings, as well). This will involve derogatory opinions of the Jackson movies as well as less harsh ones about Ralph Bakshi’s strangely appealing animated movie and even Rankin and Bass’ song-filled cartoon. I’m not sure how much anyone needs to read about Prof. Tolkien’s books at this point, but I really do feel the need to write about them. I hope you’ll follow along and tell me all your opinions about the books and movies, as well.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column the first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.