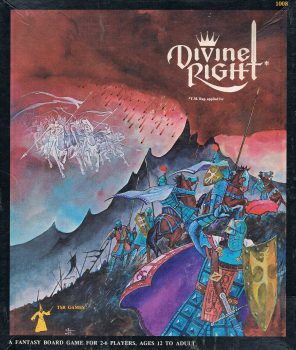

In the summer of 1981, my friend Alex R. had moved into a big, new house not far from the Staten Island neighborhood where most of my other friends lived. As his parents were rarely home and summer was beginning, we spent all our days and most nights there, watching movies and playing D&D. Things changed significantly when George K. showed up one day with a copy of TSR’s fantasy wargame, Divine Right.

In the summer of 1981, my friend Alex R. had moved into a big, new house not far from the Staten Island neighborhood where most of my other friends lived. As his parents were rarely home and summer was beginning, we spent all our days and most nights there, watching movies and playing D&D. Things changed significantly when George K. showed up one day with a copy of TSR’s fantasy wargame, Divine Right.

Designed by brothers Glenn and Kenneth Rahman, it’s from the time just before D&D had fully exploded into some approaching mass popularity and TSR was still connected to its board and wargaming roots. The Rahmans developed Divine Right from an earlier, unpublished game of theirs called Your Excellency. There were earlier fantasy wargames, White Bear and Red Moon and Elric from Chaosium and Swords and Sorcery from SPI, but for whatever reason, this is the one we encountered first and immediately fell in love with.

That first summer, we became obsessed with Divine Right. We’d start playing by noon and usually finish around dinner time. Half the days we ended up back at Alex’s for a second round. By the end of the summer, we started doing what I’ve since discovered lots of players did and made up our own house rules and new counters. We never actually put any of them into play for all sorts of reasons (primarily laziness, though), but we kept playing the game regularly for about a decade. Only when careers and families put an end to our gaming days did Divine Right get boxed up and tucked away in a cabinet in my basement.

These days, about once a year, I manage to get in a game with my friend Jim D. and his sons up in Connecticut. I am happy to report that a recent game reassured me, that even while I got murderized by Jim’s oldest son, I still play with the same take-no-prisoner approach and went down swinging. This is a game where victory is determined solely by one’s martial success, with points being awarded for sacking cities and capturing or killing monarchs.

Divine Right, as war games go, is medium complexity. Players take the roles of the kings of either one of seven human kingdoms, four non-human kingdoms — elves, trolls, dwarfs, goblins — or two sorcerous factions, the Eaters of Wisdom or the Black Hand, and then spend the game trying to wipe each other out.

Divine Right, as war games go, is medium complexity. Players take the roles of the kings of either one of seven human kingdoms, four non-human kingdoms — elves, trolls, dwarfs, goblins — or two sorcerous factions, the Eaters of Wisdom or the Black Hand, and then spend the game trying to wipe each other out.

The game’s setting is the world of Minaria. The history of the land, its kingdoms, and several of the special mercenaries was described in great detail by Glenn Rahman in a series of articles titled Minarian Legends in The Dragon Magazine. Reading them isn’t needed to play the game, but they give Minaria so much more depth than most fantasy game settings.

The various powers vary in strength, some having large armies or navies, and others having smaller forces but more readily defendable terrain. The trolls and dwarves start scattered around the border in several small, but unified, regions. The two magical powers have few ground forces, instead, they must rely on their arsenals of spells and magical devices.

Each game of twenty turns represents one campaign season. The turn sequence is straightforward:

Each game of twenty turns represents one campaign season. The turn sequence is straightforward:

Player Order Determination

First Player Turn

- Random Events

- Draw Diplomacy Cared

- Conduct Diplomacy

- Resolve Sieges

- Movement

- Combat

Random events range from plagues and desertions afflicting one’s armies to the sudden alliance of a previously neutral power. The diplomacy cards either add to the attempt to ally with neutral powers or allow the deployment of special mercenaries. These include assorted generals, a dragon, a sea monster, the Romani-like Wandering People, and other valuable forces.

It’s in the diplomatic phase where the player can build up his power if he’s to have a chance of winning. The main method is to send his ambassador to a neutral court. A roll of six or better as modified by a diplomacy card secures an alliance.

One’s ambassador can take other actions. At the risk of being burned at the stake, they can recruit barbarian hordes from the uncivilized edges of the map. They can also, once a game, attempt to assassinate another player’s ambassador, taking them out of the game for several turns. That can be a heavy blow for a monarch facing imminent invasion with insufficient armies to guard the borders.

Sieges are the most complex part of the game. Armies equal to or greater than the defensive value of a castle and its defenders must form a zone of siege around it. Then the sieging player must roll a six or better as modified by the ratio of forces. There are a few special modifies, including the mercenary, Ogsbogg the Ogre. He’s a siege specialist who uses a ship’s chain and anchor to break down castle walls.

Movement is simple. Each army’s movement factor is printed in the upper right corner. Along with it are symbols on some units indicating the ability to move more easily through difficult terrain. For example, dwarves are slowed by hills and don’t have to stop in mountains. Elves, of course, just breeze through the woods. Rugged terrain can be important for defense, forcing attackers to channel their forces and making attacks more costly.

Along with movement, combat is at the heart of the game. It occupies the most game time and if sieges are to be successful and monarchs captured or killed, this is how it’s done. Each player in a battle rolls a die. Again, there are modifiers based on the ratio of forces, the presence of special mercenaries, and magical items. The low roll loses units equal to the difference in die rolls. A tie means equal losses for both sides. Many a time I’ve seen a pair of sixes rolled absolutely overturn a player’s carefully planned attack and completely reverse the situation.

The game is loaded with layers of chrome that give depth to the game and increase the options open to players. At the south edge of the board, there’s the Altar of Graystaff. Sacrifice an army and win a magical item. To the north lies the Temple of Kings. Bold monarchs can visit it and roll a die. On a two through five, they win a powerful artifact. A six means enchanted sleep and a one means death. I know many players who bet their whole fate on that single roll and come out lucky. Plenty who didn’t, too.

In my experience, most players have the same strategy: build up their forces and then swoop in on the weakest opponent. You can go after neutral powers, but then they immediately ally with another player. The problem, of course, is that everyone might look like the weakest opponent to some other player. Once a player looks like their losing, there’s a chance every other player will turn on him, looking for easy victory points. And this, in turn, can leave an attacker’s cities open to attack from somewhere else. Most games turn into a free-for-all, grand melee by the midpoint, and it’s awesome.

My friends and I were drawn to the game by its fantasy setting first. We also all had some experience with wargames like Third Reich and Panzer Blitz. What led to our obsession that first summer was the sheer fun we had playing against each other and creating characters. Rombune was founded by pirates, so whoever got them talked like Long John Silver (this was decades before Johnny Depp corrupted pirate movies). At some point, it became accepted by everyone that the Black Hand sounded like the Count from Sesame Street and had a general named Larry who was missing his bottom jaw. Larry’s response to every command was an unintelligible, distressed groan. By that summer we had already rejected all the rule-playing and power gaming of our original gaming crowd in favor of more character-based roleplaying so we naturally mixed that into our Divine Right games. We brought that same style to other games like Illuminati, Cosmic Encounters, and Junta, but never to the same degree or goofiness as with Divine Right. Looking back forty-three years, it was something really special.

My friends and I were drawn to the game by its fantasy setting first. We also all had some experience with wargames like Third Reich and Panzer Blitz. What led to our obsession that first summer was the sheer fun we had playing against each other and creating characters. Rombune was founded by pirates, so whoever got them talked like Long John Silver (this was decades before Johnny Depp corrupted pirate movies). At some point, it became accepted by everyone that the Black Hand sounded like the Count from Sesame Street and had a general named Larry who was missing his bottom jaw. Larry’s response to every command was an unintelligible, distressed groan. By that summer we had already rejected all the rule-playing and power gaming of our original gaming crowd in favor of more character-based roleplaying so we naturally mixed that into our Divine Right games. We brought that same style to other games like Illuminati, Cosmic Encounters, and Junta, but never to the same degree or goofiness as with Divine Right. Looking back forty-three years, it was something really special.

There were rumors of a new version of the game, The Scarlet Empire, that surfaced but never came to fruition. You can see the game test map on Boardgame Geek. In 2002, Right Stuf released a 25th Anniversary edition. I picked it up, but it’s not great. It’s got a hard board, but the original colors were changed to poorer ones and reading the information on the glossy finish is difficult. The vast quantity of new, advanced rules look enticing but turn out to be burdensome. The rulebook is an unholy mess, making everything worse. Still, it’s the game Jim D. and I used a few weeks ago and we made it work.

What’s triggered my sudden nostalgia for the game was two-fold. First, one of my nephews and his friend were staying over this summer and wanted to play a game. They play a little D&D and jumped at the copy of Divine Right. We played most of a game and they might have had more fun than I did. While looking up some rules clarifications, we discovered that there’s a new edition coming out shortly. Worthington Games has what looks to a be beautiful edition, complete with a return to the original colors and artwork. The flimsy little paper cards from the original are being replaced with playing card-sized cards on cardstock. My interest was piqued.

The thing is, I haven’t ordered a copy. I might later, but both my nephew, his friend, and Jim and his sons have all pre-ordered the game. You can find pre-owned but decent-looking copies of the original game for under a hundred dollars, but that new version looks pretty terrific. I know it’s what I’ll be playing come the new year.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Sunday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.