The human mind daydreams its way around certain specific topics with exceptional regularity. We fret about personal security, we hope for love (in its innumerable forms), and to round out the likely top three, we focus on death. This last in particular invites a speculative element: we can hardly help fantasizing about an extended or perhaps immortal life span.

But not far down the list comes the earnest desire to travel in time. Backward, forward, sidelong –– “over, under, sideways, down” –– any shift in our current path will do. We want to zip back in time to visit places now impossible to see, or connect with loved ones we’ve lost. We want to zoom forward to get a preview of what is to come.

The urge is powerful, atavistic. It’s as if our very cells, so prone to decay (a driving force of time as we experience it), insist that here lies a field that demands investigation.

I don’t pretend to have read every book that tackles the subject –– no one has –– but I’ve dipped my toes into the sci-fi waters often enough that I can’t help but be struck by the many-splendored visions we foolish mortals have of how time travel might work.

H.G. Wells, in The Time Machine, imagines a mechanism essentially similar to a car in that you sit down in it, and it takes you where you want to go. Provided you direct it properly, it goes where and when you wish. I haven’t read The Time Machine for something like forty years, but as I recall, slippery questions like what the machine scoops up in its wake (airborne pathogens, for example) don’t come into play.

A Sound of Thunder and Other Stories by Ray Bradbury

(Harper Perennial, July 2005). Cover artist unknown

Ray Bradbury rears his head with “A Sound of Thunder,” in which time travel involves a sort of levitating pathway, not unlike a boardwalk crossing a swamp, but without the pylons. So long as you stay on the boardwalk and don’t get off, your ability to interact with the time period you’re visiting is strictly voyeuristic.

For those who haven’t read this seminal short, I’m not giving anything away by acknowledging that Bradbury’s hero (of course!) fails to stay on the boardwalk. Given the set-up, that much is guaranteed. What happens next? Well, it’s election season (again). Stay tuned and find out.

Time and Again by Jack Finney (Fireside Books,

January 1986). Cover artist unknown

But time travel can be far less mechanistic. Jack Finney, in Time and Again, concludes that traveling back (not forward) in time is simply a matter of two things: willpower and detail. To quote my middle-school art teacher, “If you can see it, you can paint it.”

So, for Finney’s heroes, all you need do in order to visit New York City’s Victorian era is to dream yourself there –– to surround yourself with the necessary visual and auditory trappings, and concentrate like the devil. When you wake, there you will be, in the past.

This is How You Love the Time War by Amal El-Mohtar

and Max Gladstone (Saga Press, July 6, 2019)

For Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone, time travel is about clambering up and down various “threads” of time, then hopping from one to the next as needed. It’s clear from This is How You Lose the Time War that only certain persons have this skill, but if you’ve got it, time is an open book. It’s a winding, vine-like maze you can get lost in, but with this essential condition: the braids of time are manifold, and diverge at certain key points. As with Bradbury, the outcomes of the future can be changed, altered –– and not necessarily for the good.

Finney and Wells evince no such concern. Time travel for them is hermetic, and time itself is a unity. It moves in its course, beginning to end, and one visits with no particular concern for one’s personal impact. “Leave Only Footprints, Take Only Pictures” isn’t a sign the Time Travel Parks Police need deploy in these versions of reality, since time isn’t environmentally sensitive.

Compare to Connie Willis and her Oxford Time Travel Series, where time is finicky. If you move around in it, time pushes back. Arrive near a particularly delicate moment, one where various time streams might split off, and time reacts like a live, semi-sentient creature. It actively defends itself against paradoxes, and causes “slippage” such that any given time-traveler arrives hours or even months after (or before) any given inflection point, in order to prevent unwitting damage.

This is certainly the case in To Say Nothing of the Dog, treated here, and in The Doomsday Book. I assume the rule holds true in All Clear and Blackout, the other two tomes in the Oxford sequence, but those I haven’t read.

The Time Machine by H.G. Wells

Of course, we are all of us time travelers. As a friend of mine who teaches science tells his students when they ask about the possibilities of time travel, “You’re traveling through time right now. Forward.”

More than one writer has attempted to chart what happens when that motion gets reversed or arrested. Hyperion, by Dan Simmons, wreaks emotional havoc with the reader by aging a grown woman backward so that she becomes younger to the point of infancy. Plying a similar trade, T.H. White famously provided Merlin with a comic edge (and endless befuddlement) by having him age backward, without going into any useful detail about how, exactly, this would work.

And then there are those for whom time simply ceases to apply. Winnie, in Natalie Babbitt’s Tuck Everlasting, must choose whether to drink from a spring that will stop her from aging, apparently forever. Babbitt builds up to Winnie’s decision with a naturalist’s eye, focusing on the seasons and the wild things of the world, which are, of course, forever in flux.

Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut

(Dell, 1972). Cover artist unknown.

Kurt Vonnegut’s approach was to simply untether his fictional hero from any kind of consistent temporal placement. “Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time,” is how Vonnegut put it, in Slaughterhouse Five. The author then has free reign to move him about like a chess piece, dropping him here, pinning him there.

As with Billy Pilgrim, Dana, in Octavia Butler’s Kindred, has no control over her trips backward to the early 1800s. It’s as if time grabs hold of her, a literal seizure, then deposits her where it wills. Time, in Butler’s hands, is a violent kidnapper.

For myself, my main argument with time comes down to how to hoard it, store it, and save it for the moments when I can (supposedly) put my feet up and dive into a good book.

May we all, gentle readers, enjoy that particular brand of quality time.

Onward!

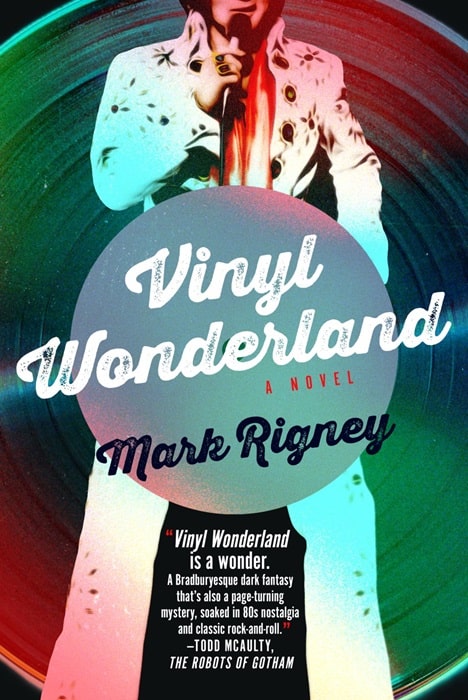

Mark Rigney is a writer and long-time Black Gate blogger. His work on this site includes original fiction and perennially popular posts like “Youth in a Box.” His new novel, Vinyl Wonderland, dropped on June 25th, 2024. Reviewer Rich Horton said of Vinyl Wonderland, “I was brought to tears, tears I trusted. A lovely work.” His favorite review quote so far comes from Instagram: “Holy crap on a cracker, it’s so good.” A preview post can be found HERE, while his website lives over THERE.